Place and Space: Walking with Constable

by Andy Corrigan

‘Place’ and ‘space’ have long been an evocative duo; inspiration to many a creative, probed by many a philosopher or scientist, and much like that other influential proposition, ‘time’, are tangible and relatable to all of our daily lives. Time might not have changed a great deal lately, but our relationship to place and space has perhaps seen one of the biggest impacts of the ever-quickening pace of the digital information age.

Digital tools and methods, in particular global positioning systems (GPS), enable all sorts of innovative approaches, and it is the prominence of these that places them at the front of the queue when reflecting on place and space. But is our overwhelming fascination with exactly where we’ve been, where we are or where we might go, superficially distracting us from something deeper, more visceral? Is the enchanting prospect of transporting us somewhere else, somewhere virtual, so alluring that we are losing sight of the fundamental value that this interconnected world can play in our lives?

We can’t say we weren’t warned this might happen. In 1923, during a lecture, Aby Warburg invoked the Greek myths of Prometheus and Icarus when he foretold the impact that technological advances in flight, communication and electricity would have on our perception of distance:

“The modern Prometheus and the modern Icarus, Franklin and the Wright brothers, who invented the dirigible airplane, are precisely those ominous destroyers of the sense of distance, who threaten to lead the planet back into chaos.

Telegram and telephone destroy the cosmos. Mythical and symbolic thinking strive to form spiritual bonds between humanity and the surrounding world, shaping distance into the space required for devotion and reflection: the distance undone by the instantaneous electric connection.”

(Warburg, 1995)1

Have we flown too close to the sun? Perhaps he even predicted the sense of apathy many of us now feel as part of our perfunctory use of digital technology? Are we entering an inevitable era in a cycle of automation anxiety? (Bassett & Roberts, 2019)2

A few years later in his 1928 essay ‘The conquest of ubiquity’, Paul Valéry took this one step further. He predicted the internet age by suggesting that images would become abundant and so easy to hand that we’d have them on tap, pumped into our homes like the rest of our utilities (Benjamin, 2008).3 He was more known as a poet and philosopher than science fiction writer, but even in hindsight that feels like science fiction. Indeed, we’ve now turned that tool around on itself in order to study things like the influence of science fiction on technological innovation (Bassett et al, 2013).4

Valéry’s essay directly influenced Walter Benjamin, who made a slightly less mythical comparison than Warburg of likening the magician to the artist and the surgeon to cameraman, before going on to suggest the concept of multiple fragments assembled under a new law (Benjamin, 2008).3 Again, our perception of distance is challenged by the technology with which we mediate, and that is something that can inform our practice.

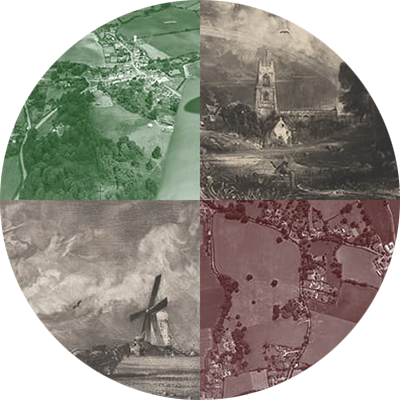

The Walking with Constable project is an unusual digital humanities (DH) project. Not least, the technology that facilitates it needed to account for the fact that we wanted to take the digital out of the archive, for a walk, where we didn’t know how reliable the connectivity would be. But through a collective embodied experience that showcases interconnectedness, the project relates digital content back to the landscape from which it was generated and questions our relationship to it in a very personal way.

I was asked if I could demonstrate how a digital project can implement theoretical and methodological approaches to “place and space”, in a practical sense, to a group of DH MPhil students. In preparation for that discussion, I gathered some of the philosophical ideas that informed the project together and thought a summary would potentially prove useful to write up for my own thinking, and so here it is.

One of the main influencers of the design of the project was the French theorist of everyday life Michel De Certeau, who argued that walking is writing. The practical link between a philosophy that poses walking as a form of writing and a project that uses this idea to take digital content for a walk is unambiguous enough, but De Certeau also helps us fill in some of the gaps in his essay on Spatial Stories, which I’ve abridged here:

“Every day [stories] traverse and organise places; they select and link them together […] they are spatial trajectories.

“Spaces” and “places”.

A place is thus an instantaneous configuration of positions. It implies an indication of stability. A space exists when one takes into consideration vectors of direction, velocities, and time variables. Thus space is composed of intersections of mobile elements. […] Everyday stories tell us what one can do in it and make out of it. They are treatments of space. […] The Story […] “turns” the frontier into a crossing, and the river into a bridge. […] From the functioning of the urban network to that of the rural landscape, there is no spatiality that is not organised by the determination of frontiers. […] What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.”

(Certeau, 1984, p. 115-130)5

Hermeneutics, of a sort, is another factor that had a place to play. How would walking with Constable influence our interpretation and understanding and of his work? When German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer took on the task of his ‘Truth and Method’, one particular point of focus around Friedrich Schleiermacher’s point that:

“The work of art loses […] significance if it is torn from its original context […] a work of art, too, is really rooted in its own soil, its own environment. It loses its meaning when it is wrenched from this environment and enters into general circulation.”

(Gadamer, 1989, p. 166)6

So, our use of augmented reality to take works that had been created for mass circulation, doubly so as we were using digitised mezzotints produced for Constable by the engraver David Lucas, speaks directly to this - we were taking those works back into the environment that made them:

“The various means of historical reconstruction - re-establishing the “world” to which it belongs, re-establishing the original situation which the creative artist “had in mind,” performing in the original style, and so on – can claim to reveal the true meaning of a work of art and guard against misunderstanding and anachronistic interpretation”

Gadamer, 1989, p. 166)6

Gadamer was also keen to remind us that:

“The essential nature of the historical spirit consists not in the restoration of the past but in thoughtful meditation with contemporary life.”

(Gadamer, 1989, p. 168)6

The Walking with Constable project invited groups of ‘publics’ to join us. Some were local, knew the landscape very well and had a great deal of knowledge and experience about it to share. Others were locals who might not know it so well, or even consider how Constable’s work might relate to them, and they also had a great deal of knowledge and experience to share.

One phase of the project explored the potential of including communities who might not usually engage with the academic research process, or even the landscape in which they live. In doing so, we walked with people from, excuse the pun, all walks of life. This also helped echo Gadamer’s emphasis on relating contemporary life and exposed the value in themes of interconnectedness and universality.

Even aspects that occurred through practicality would find parallels or nooks and crannies in aspects of theory. The embodied action of holding the paper slips with printed markers on them up to the tablet’s camera lens that called the correct digital image into augmented reality for example. This action recalled the work of photographer Kenneth Josephson, who was known for his photographs that layered pictures within pictures, once said:

“It was important for me to learn to think of the photograph as a physical object, because I had always thought of the photograph as an illusionistic space and never as a piece of paper that curls up or that you could hold. […] When you hold the photograph in a scene, it starts taking on the feel of an object”

(Josephson, 1999, p. 179 )7

As someone who leans very much towards visual language and practical understanding, I’ve never found philosophy and theory particularly easy to grapple with. But the Walking with Constable project has emboldened me with a different perspective; that just as a viewer can fluidly interpret an artwork, so too is it possible to relate to philosophy and theory. Whether I succeeded in transporting every student over the bridge that we built from theory to practice is hard to say, but there’s certainly some dense food for thought and debate. This, after all, is a journey in itself.

[Addendum 12/05/2024:] I talked to the Cambridge Digital Humanities MPhil students back in November 2023 and whilst this post was mostly written back in February, it’s taken me a while longer to get around to finishing it off. I did so last night, whilst watching 2024’s Eurovision Song Contest. I wonder what Paul Valéry would have thought of that?! I certainly found it a bit of a challenge, balancing the experience as I did with checking my quotations and citations, which would at least partially explain any errors

The writing of this post has been funded by the AHRC-RLUK Professional Practice Fellowship Scheme for research and academic libraries.

-

Warburg, A. M. (1995), Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America. Translated by M. P. Steinberg. Cornell University Press. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt1g69xgc ↩

-

Bassett, C., & Roberts, B. (2019). Automation now and then: automation fevers, anxieties and utopias (Version 1). University of Sussex. Available at https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.23474147.v1 ↩

-

Benjamin, W. (2008) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Translated by J. A. Underwood. London: Penguin Books. ↩ ↩2

-

Bassett, C. Steinmueller, E. Voss, G. (2013). Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science fiction and Innovation. Nesta Working Paper No. 13/07. Available at https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/better-made-up-the-mutual-influence-of-science-fiction-and-innovation/ ↩

-

Certeau, Michel de. (1984). The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by S. Rendall. University of California Press. ↩

-

Gadamer, H.G. (1989). Truth and Method (2nd revised edition). Translated by J. Weinsheimer and D. Marshall. London: Sheed & Ward. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Josephson, K. Interview with Stephanie Lipscomb. Recorded between 1998 and 1999. Printed in Wolf, S. (1999) Kenneth Josephson: A Retrospective. The Art Institute of Chicago. ↩