Blake's Universe

by Andy Corrigan

Rediscovering a forgotten bridge and taking the scenic route for an inspiring wander with a waft of the warmth of harmony.

There are several names that keep cropping up, calling through various cracks in different ways, and one of them is William Blake. The Fitzwilliam Museum’s exhibition ‘William Blake’s Universe’ ran from 23 February – 19 May 2024. It described itself as “timely”, hinting at a contemporary urge to seek spirituality in response to the turbulent times in which we currently find ourselves. Are they ever not turbulent? Regardless, the exhibition was clearly timely for me as it provided an opportunity to delve a little deeper into Blake’s universe as I excavated those cracks through which he was emerging.

Of course, being perhaps less timely, I’d left it until the last day the exhibition was open to go and see it. After urging myself into action and initiating my journey into Cambridge, the realisation dawned that I was on my way, I was going to make it to the museum, and didn’t need to rush. I could relax. As I strolled down from the University Library, this liberation led to a series of decisions that drew me to avoid the usual more direct route I might walk to Fitzwilliam and seek out a quieter route; one less trodden.

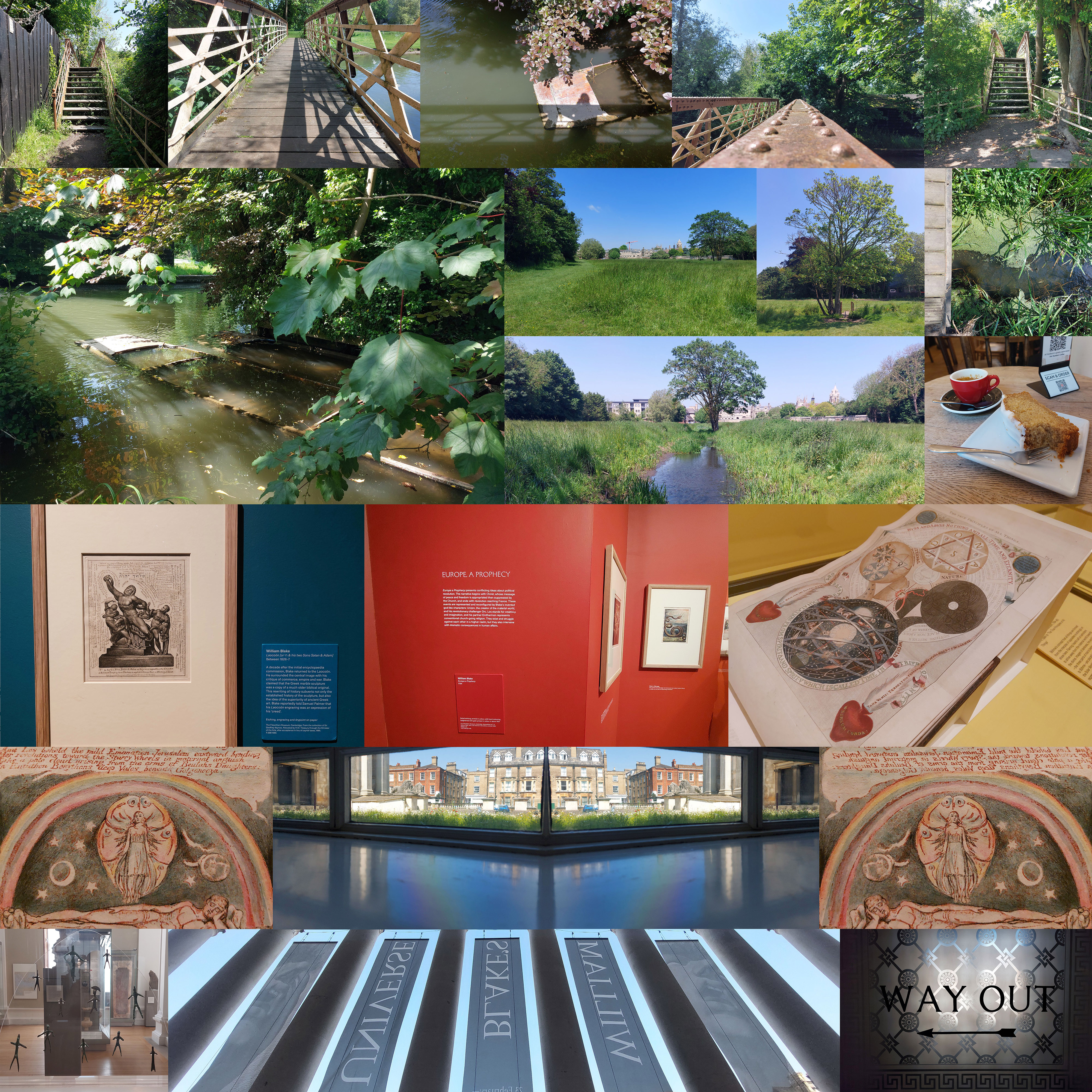

As I made my way across Sheep’s Green, I remembered the somewhat hidden and neglected footbridge that crosses the Cam and leads into Coe Fen. It seems the bridge is not the only forgotten thing - a sunken punt lies rotting in a cranny in the river bank like an elegant old shipwreck. I was rewarded with that sense of how easy it is to feel external to the city in Cambridge whilst being, in this time at least, really quite central. In case the calming sense of having arrived via a slower, more contemplative and tranquil route, wasn’t quite adequate in preparing myself, I also decided to stop and arm myself by having a coffee and a slice of cake.

– A collage of photos from my walk to Blake’s Universe

Initially a little underwhelmed by the monotonous palette of the works in the first ‘blue’ room, it took a while to orientate myself amongst what felt like a busy space, both in terms of navigating the number of people there, and the curatorial intent. It felt like a beginning, the start of the story, the preparation for the journey. On recovering from the initial shock of this sudden busyness after my pastoral pilgrimage, and a bit of ambling around the space, things began to settle, and I started to find focus.

In addition to its role as a starting point to the exhibition, for me this blue room emphasised the importance of simplicity, of learning from what came before in order to prepare yourself for what is to come. The blurring of boundaries begins:

- Images and words.

- Body and soul

- Past and present.

- Fact and myth

- Observation and imagination

Works, themes, names, nodes perhaps, began to stand out. The idea of recontextualization that subtly emanates from ‘The Reposing Traveller’ and the sense of Blake’s journey in a search for meaning. Another name that’s been cropping up elsewhere in my research is Thomas Gray, whose practice of keeping commonplace notebooks is another working practice I’ve been encountering. On delving a bit deeper, I came across a notebook, now in the British Library, that Blake sporadically used a between 1787-1818. ‘The William Blake Archive’ describe how Blake “crammed its nooks and crannies” in a manner far less methodically than Gray’s more formal methodical approach. The other theme laid bare from this beginning, is one of Blake embracing complexity and interconnectedness in his search for sense amongst chaos. I was particularly drawn in this respect to his ‘Laocoön’, reportedly “an expression of his ‘creed’.”

Things visually and prophetically heat up in the next, ‘orange and red’, room as the complexities and chaos of society in the late C18th interweaves:

- State and church

- War and peace

- Revolution and tradition

- Patterns of human history

- Freedom and captivity

- Lightness and darkness

- The physical and the imagination

Classical and religious imagery visually harmonises with folkloric voices joining the ensemble, and nature providing a uniting cadence to proceedings. Perhaps prophesising the later Victorian fascination with folklore, or perhaps this particular harmony is just timelessly British? As our journey progresses in the company of a host angels, fairies and orcs, the universality and strength of nature to overcome the oppressive forces of humanity – the church, the state, our understanding and our control.

A cheerful harmonious yellow draws me away from the hot red calamity of the orange/red room, and on into a more positive feeling C19th, accompanied by Faith, Hope and Charity. Despite this positive progress, the value of looking back is not lost – positivity seemingly to be discovered through the influence of Jacob Bohme in balancing opposites to reveal/create unity and harmony. Naturally of course, this involves a great deal of circles, which is another theme that has been ever present in my research.

The pinnacle of this harmony, and Blake’s work, is of course a reconciliation between Jerusalem and ‘Albion’. Before I leave, I’m reminded that this state of harmony is only made possible through continual spiritual, creative and mental renewal. This seems perfectly apt given the direction my research is taking me and the adventure/journey I’m on. I picked up a copy of Blake’s ‘Songs of Innocence and of Experience’ in the museum shop - it seems a felicitous encapsulation with which to become better acquainted. The Fitzwilliam Museum also produced this reading of ‘The Tyger’ by Salena Godden, in which she shares what it is that draws her to William Blake and touches on a more subtle aspect - the relevance of “feeling”.

My eye catches a rainbow, cast on a windowsill by the first view of the outside world, as I leave the exhibition and weave my way out through the other galleries at the museum in order to maximise the chance of any potential encounters as my mind spun around in its orbit of Blake’s universe. The other thing that catches my attention are some seemingly floating bronze votive figures from pre-Roman Umbria. A reminder of humanities capacity to embrace anthropological fetishism and the complex nature of our relationship to things we don’t understand.